Science

Interdisciplinary Team Identifies Black Death Mass Grave Near Erfurt

A team of researchers from Leipzig University has uncovered significant evidence of a mass grave linked to the Black Death near the abandoned medieval village of Neuses, situated outside Erfurt, Germany. This discovery marks the first systematically identified burial site associated with plague victims in Europe, shedding new light on one of history’s most devastating pandemics.

The study, conducted with the assistance of the Leibniz Institute for the History and Culture of Eastern Europe (GWZO) and the Helmholtz Center for Environmental Research (UFZ), has been published in the journal PLOS One. The team employed a combination of historical documentation, geophysical measurements, and sediment coring techniques to locate a burial structure that matches descriptions of plague pits from 14th-century records.

Tracing the Black Death’s Impact on Europe

Between 1346 and 1353, the Black Death claimed the lives of an estimated 25 million people in Europe, nearly half of the continent’s population at the time. In Central Europe, the region of Thuringia was among the hardest hit. Historical records indicate that approximately 12,000 people were interred in eleven large pits near Erfurt during the outbreak in 1350. Until now, the precise locations of these burial sites remained unknown.

Using advanced techniques such as electrical resistivity mapping, the researchers reconstructed the medieval land surface and identified a subsurface structure measuring approximately 10 m × 15 m × 3.5 m. This structure contained mixed sediments and fragments of human remains. Radiocarbon dating confirmed that the human remains date back to the 14th century.

“Our results strongly suggest that we have pinpointed one of the plague mass graves described in the Erfurt chronicles,” stated Dr. Michael Hein, the lead author and a geographer at Leipzig University. He emphasized that while the findings are promising, definitive confirmation will require planned archaeological excavation.

Understanding Historical Burial Practices

The research highlights how natural soil conditions influenced settlement patterns and burial practices during the Middle Ages. The site of Neuses, along the drier zone of the River Gera, was deemed more suitable for burials compared to the wetter floodplain soils, where decomposition occurs at a slower rate.

“This finding aligns with both modern soil science and the medieval ‘miasma theory,'” noted Dr. Martin Bauch from GWZO. He explained that the perception of disease transmission through ‘bad air’ led to the preference for burials located far from city centers, a factor also influenced by legal and political considerations.

By integrating historical, geophysical, and soil science methodologies, the team successfully utilized the landscape as an archive. This interdisciplinary approach not only aids in identifying historical mass graves but may also help protect against the loss of such sites in the future.

The discovery of this mass grave is particularly significant as confirmed Black Death burial sites are exceedingly rare, with fewer than ten known across Europe. This site near Erfurt adds a vital chapter to the city’s medieval history, which gained recognition when it was designated a UNESCO World Heritage site in 2023.

The implications of this research extend beyond historical inquiry. It opens avenues for genetic and anthropological studies that could reveal insights into the evolution of the pathogen Yersinia pestis, the causes of high mortality rates during the 14th century, and how societies managed epidemic challenges.

In collaboration with the Thuringian State Office for Heritage Management and Archaeology, further excavations are already in the pipeline. These excavations will provide additional materials for genetic analyses at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology (MPI-EVA) in Leipzig.

“This discovery is not only of archaeological and historical importance,” said Professor Christoph Zielhofer, head of the Historical Anthropospheres research group at Leipzig University’s LeipzigLab. “It helps us understand how societies deal with mass mortality—and how modern interdisciplinary science can contribute to locating mass graves, topics that remain relevant even in the 21st century.”

-

Science3 months ago

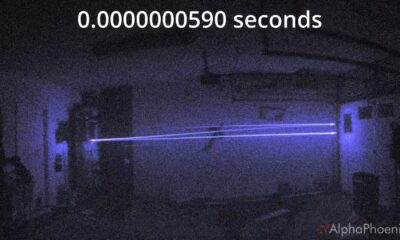

Science3 months agoInventor Achieves Breakthrough with 2 Billion FPS Laser Video

-

Health3 months ago

Health3 months agoCommunity Unites for 7th Annual Into the Light Walk for Mental Health

-

Top Stories3 months ago

Top Stories3 months agoCharlie Sheen’s New Romance: ‘Glowing’ with Younger Partner

-

Entertainment3 months ago

Entertainment3 months agoDua Lipa Aces GCSE Spanish, Sparks Super Bowl Buzz with Fans

-

Entertainment3 months ago

Entertainment3 months agoMother Fights to Reunite with Children After Kidnapping in New Drama

-

Science1 month ago

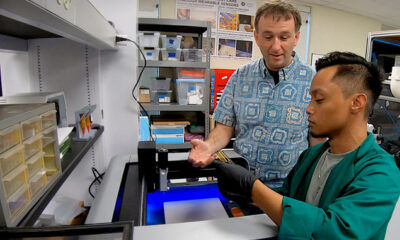

Science1 month agoResearchers Launch $1.25M Project for Real-Time Hazard Monitoring in Hawaiʻi

-

Top Stories3 months ago

Top Stories3 months agoFormer Mozilla CMO Launches AI-Driven Cannabis Cocktail Brand Fast

-

World3 months ago

World3 months agoR&B Icon D’Angelo Dies at 51, Leaving Lasting Legacy

-

Health3 months ago

Health3 months agoParenting Pitfalls: 16 Small Mistakes with Long-Term Effects

-

Health3 months ago

Health3 months agoCurium Group, PeptiDream, and PDRadiopharma Launch Key Cancer Trial

-

Science3 months ago

Science3 months agoAI Gun Detection System Mistakes Doritos for Weapon, Sparks Outrage

-

Entertainment3 months ago

Entertainment3 months agoOlivia Plath Opens Up About Her Marriage Struggles and Divorce