Politics

Historic Return of Raven Helmet to Kiks.ádi After 100 Years

A significant cultural artifact, the Raven helmet from the Battle of Sitka, is set to return to the Kiks.ádi people after over a century in state possession. This decision, made by the Alaska State Museums, marks a pivotal moment in the ongoing efforts to repatriate sacred items to Indigenous communities.

The Kiks.ádi, a clan of the Lingít people, have long asserted that the helmet was never the rightful property of the state. The helmet, crafted by a Kiks.ádi warrior named Ḵ’alyáan, was worn during battles against Russian colonists in the early 1800s. These struggles remain emblematic of Lingít resistance to colonialism. For the past 200 years, the Kiks.ádi have sought the return of this at.oow, a term that describes sacred clan items imbued with spiritual significance.

The helmet has been housed at the Sheldon Jackson Museum in Sitka since 1906, where it has been displayed behind glass. Aanyaanáxch Ray Wilson, the Kiks.ádi clan leader, emphasized the importance of such items, stating, “At.oow hold spirits, and clan members treat them like relatives.” He expressed the emotional toll of the helmet’s absence, saying, “It’s really hard to accept… it belongs to us.”

Wilson, now 92 years old, reflected on the impact of colonialism on Lingít cultural practices. He noted that restoring at.oow to ceremonies can help mend the fractures caused by historical injustices. “The main thing is that it’s coming back to help our people. We all need help,” he said, highlighting the urgency of cultural revitalization in challenging times.

The history of the Raven helmet’s journey to the museum is complex. Three Kiks.ádi men, including a descendant of Ḵ’alyáan, presented it to Alaska’s Territorial Governor, John Brady, in the early 1900s. Brady co-founded the Presbyterian-run Sitka Industrial and Training School, which later became the Sheldon Jackson College. The Alaska State Museums acquired the museum and its collection in the 1980s.

For decades, Kiks.ádi leaders have argued that sacred clan items cannot be given away without the clan’s consent. A recent petition for repatriation from the Kiks.ádi emphasizes that at.oow are considered cultural patrimony, meaning they are collectively owned by clan members.

In March 2024, the Alaska State Museums agreed to initiate the process of returning the helmet to the Kiks.ádi. A spokesperson for the museum stated that they are committed to fostering collaborative relationships with the Sitka Tribe of Alaska, underscoring the significance of the repatriation as part of broader efforts to address historical wrongs.

Clan member Lduteen Jerrick Hope-Lang has been a vocal advocate for the helmet’s return, following in the footsteps of his grandmother, who sought the same outcome two decades ago. “If you’re asserting you have the right to anything, there must be proof,” he remarked, detailing the meticulous research undertaken to trace the helmet’s ownership history.

Hope-Lang collaborated with Jermaine Ross-Allam, director of the Presbyterian church’s Center for Repair of Historical Harms, to examine archival records. Ross-Allam highlighted that the church had no legitimate claim to the helmet, as the transfer lacked proper protocols. “The church never had a right to the helmet in the first place,” he concluded.

Reflecting on the historical dismissal of his grandmother’s requests, Hope-Lang expressed the emotional toll that past injustices have taken on the Kiks.ádi. “When you look at the letters… the way that she was spoken to… that’s still painful to read,” he said.

As the return of the helmet approaches, Hope-Lang remains hopeful for the future. He envisions a time when the Kiks.ádi will reclaim their cultural heritage fully. “This changes the narrative,” he explained. “When you go in and look at this piece, you’re not saying it belongs to somebody else; it belongs to you.”

Yeidikook’áa Brady-Howard, chairwoman of the Sitka Tribe of Alaska, noted that the return of the Raven helmet is part of a broader movement to reclaim sacred items scattered across the country. “Those items are literally our ancestors living away from their homeland,” she remarked, emphasizing the importance of addressing the historical context of colonialism and trauma.

The Alaska State Museums has outlined several steps to complete the repatriation process, including submitting a notice to the Federal Registrar to formally acknowledge the intent to return the helmet. As the Kiks.ádi prepare to welcome this sacred item back into their community, the significance of this event resonates far beyond a single artifact—it represents a step toward healing and reconciliation for Indigenous peoples and their histories.

-

Science2 months ago

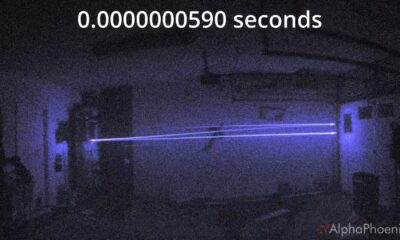

Science2 months agoInventor Achieves Breakthrough with 2 Billion FPS Laser Video

-

Health2 months ago

Health2 months agoCommunity Unites for 7th Annual Into the Light Walk for Mental Health

-

Top Stories2 months ago

Top Stories2 months agoCharlie Sheen’s New Romance: ‘Glowing’ with Younger Partner

-

Entertainment2 months ago

Entertainment2 months agoDua Lipa Aces GCSE Spanish, Sparks Super Bowl Buzz with Fans

-

Health2 months ago

Health2 months agoCurium Group, PeptiDream, and PDRadiopharma Launch Key Cancer Trial

-

Top Stories2 months ago

Top Stories2 months agoFormer Mozilla CMO Launches AI-Driven Cannabis Cocktail Brand Fast

-

Entertainment2 months ago

Entertainment2 months agoMother Fights to Reunite with Children After Kidnapping in New Drama

-

World2 months ago

World2 months agoIsrael Reopens Rafah Crossing After Hostage Remains Returned

-

World2 months ago

World2 months agoR&B Icon D’Angelo Dies at 51, Leaving Lasting Legacy

-

Business2 months ago

Business2 months agoTyler Technologies Set to Reveal Q3 Earnings on October 22

-

Health2 months ago

Health2 months agoYouTube Launches New Mental Health Tools for Teen Users

-

Health2 months ago

Health2 months agoNorth Carolina’s Biotech Boom: Billions in New Investments